Thursday, June 12, 2014

Old Bestsellers: The Man in Lower Ten, by Mary Roberts Rinehart

The Man in Lower Ten, by Mary Roberts Rinehart

a review by Rich Horton

Mary Roberts Rinehart (1876-1958) was a very popular mystery/suspense writer in her time, and her fame, while slowly dwindling, seems to me, has not disappeared. I certainly was aware of her in the '70s when I was reading Agatha Christie and the like. I confess I'd have guessed she was closer to a contemporary of Christie's, and that she was still alive in the '70s. (For that matter, I sometimes have confused her with Mary Higgins Clark.) Rinehart was often called "the American Christie", but that was really unfair to her, as she started 15 years or so before Christie (who was 12 years her junior) and was quite popular well before Christie even began writing.

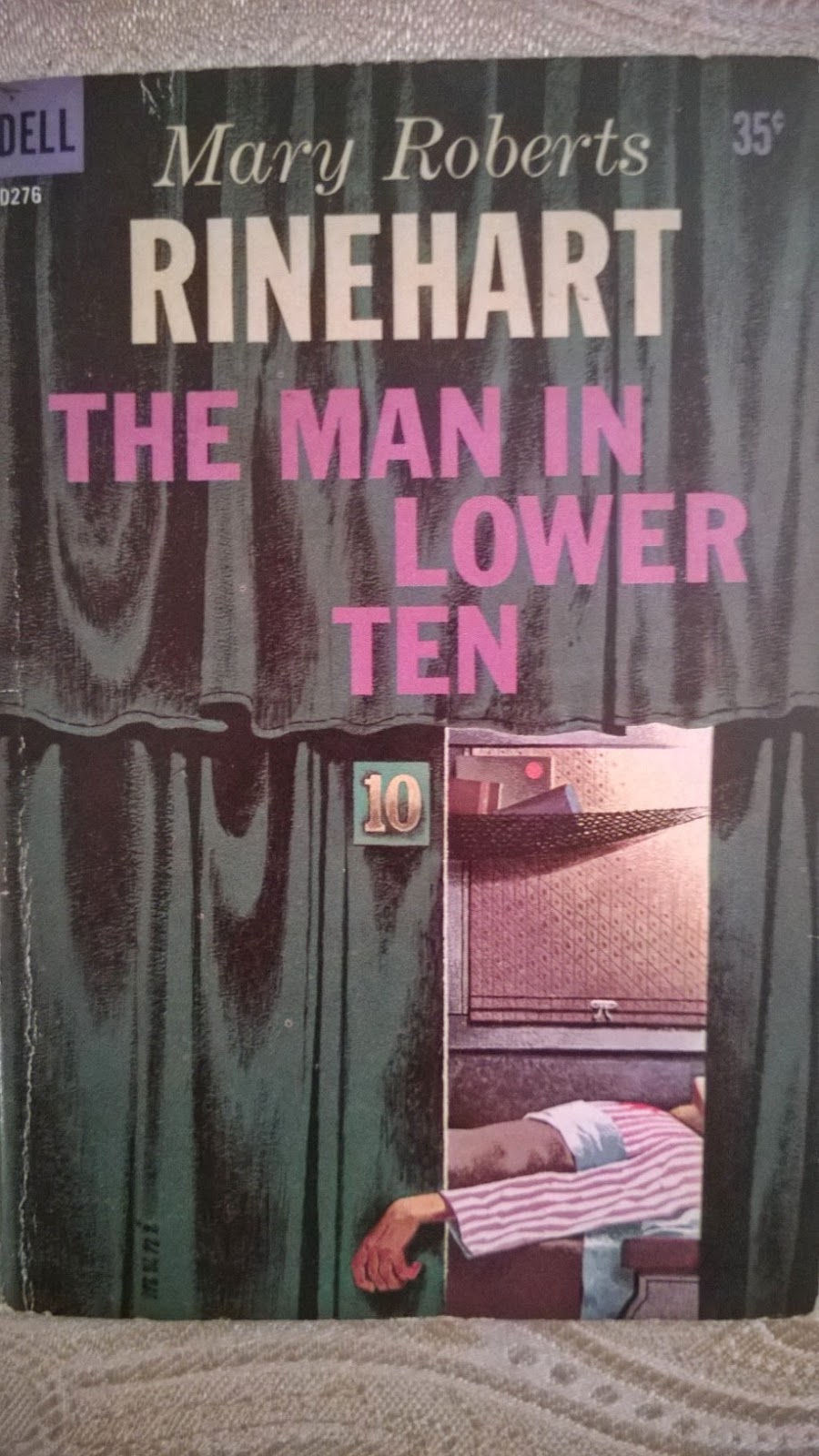

Rinehart was born in (what is now) Pittsburgh, trained to be a nurse, and married a doctor, Stanley Rinehart. She began publishing stories in the downmarket magazines of the time in 1904, to help her family's finances after the stock market crash of 1903. Her first novel was the one covered here, The Man in Lower Ten, which was serialized in All-Story Magazine in 1906. (Her second novel, The Circular Staircase (1907) is often sloppily called her first, as it was the first to become a book.) The Man in Lower Ten was published in book form in 1909, and it was the fourth bestselling novel of that year according to Publishers' Weekly. It is considered the first novel clearly in the mystery genre to become a general fiction bestseller. My copy is a 1959 Dell paperback, complete with interior illustrations.

A bit later I ran across an early hardcover reprint as well -- I had hoped on first seeing it that it might be a first edition, but instead it's a Grosset and Dunlap reprint from perhaps 1913. It is also illustrated, by Howard Chandler Christy. I've reproduced (in photographs by my son Geoff) the cover, and title page with frontispiece, below:

Rinehart diversified somewhat in later years, writing Broadway comedies, nurse fiction, and mainstream novels. (The latter apparently at the urging of her husband, who seems to have been a bit ashamed of her reputation as a trashy genre writer. He also apparently eventually resented the fact that she made much more money than he did.) By the end though she returned most often to mystery/suspense stories, and those are by far her best remembered works. I can recommend an excellent website by Michael Grost (mikegrost.com/rinehart.htm) for a detailed analysis of her career.

One tidbit about Rinehart that is often repeated is that she originated the phrase "The butler did it". This is untrue, though in one of her better known novels the butler is indeed the murderer. But there were novels and stories in which the butler was the murderer before that, and she never used that exact phrase.

According to Grost, her first two novels, The Man in Lower Ten and The Circular Staircase, may be her best. I can't comment -- The Man in Lower Ten is the only novel of hers I've read. But it is pretty decent work.

Lawrence Blakely is a Washington, DC, lawyer. His partner, Richey McKnight, inveigles him into taking a trip to Pittsburgh to take a deposition from a rich old man in a forgery case. It seems McKnight has a date with a girlfriend. Girls are famously of no particular interest to Blakeley ...

On the way back from Pittsburgh, strange things happen. There is repeated confusion over which bunk Blakely has engaged. There are a couple of interesting seeming people on the train. Blakely ends up forced into another bunk by a drunk passenger, and when he wakes up, his bag -- with the critical deposition -- and also his clothes are gone. He is forced to dress in another man's clothes, and in searching for his bag he discovers a murdered man.

Almost immediately Blakely is the prime suspect -- but before anything further happens the train crashes. Blakely is thrown free, and indeed is one of only four survivors, sustaining only a broken arm. He and another survivor, a beautiful young woman, Alison West, escape to a farmhouse where something unusual happens that Blakely doesn't understand for some time. He does realize, however, that a) Alison West is the granddaughter of the rich old man from whom he took the deposition; b) she is another prime suspect in the murder; and c) he is in love with her.

Blakely returns to DC but soon his troubles multiply. The police are lurking around his house. Another survivor from the wreck fancies himself an amateur detective and insists on investigating the otherwise almost moot murder case (after all, the witnesses are mostly dead and the victim could have been written off as merely another casualty of the train crash). Someone seems to be lurking in the house next door. And, finally, it seems that Alison West is the girl whom his partner McKnight has been seeing.

The shape of the resolution is not surprising, and indeed the solution to the primary crime, while not ridiculous, does seem a bit strained. But the novel bounces along nicely enough. Lawrence Blakely is not exactly a convincing three-dimensional character, but he's still kind of intriguing, and his voice, as teller of the story, is effective. Rinehart's writing is not brilliant, but it's solid storytelling prose, with some good turns of phrase. She does slip once or twice (for example, Blakely's arm heals for a brief passage before returning to its broken state), but really it's a solid professional effort. I liked it, though I have to say, not enough to make a special effort to seek out more of Rinehart's work.

Thursday, June 5, 2014

Old Bestsellers: The King's Jackal, by Richard Harding Davis

The King's Jackal, by Richard Harding Davis

The King's Jackal, by Richard Harding Davisa review by Rich Horton

Richard Harding Davis (1864-1916) was the son of Rebecca Harding Davis, a fairly well-known and significant writer in her day. His father was a journalist, editor of the Philadelphia Public Ledger. So perhaps it's not a surprise that Richard became a very famous journalist and novelist. He was something of a football star in his abbreviated college days (this would have been very early indeed in the history of American football). After being invited to leave two colleges (Lehigh and Johns Hopkins) he became a journalist, gaining a reputation for a flamboyant style and for tackling controversial subjects. (All this from Wikipedia.)

He became a leading war correspondent, and was particularly noted for helping to create the legend of Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders, and also for his reports on the Boer War. He was also strikingly good looking (so I judge from the picture on his Wikipedia page), and was credited for popularizing the clean-shaven look, and as the model for the the "Gibson Man", the analog to his friend Charles Dana Gibson's "Gibson Girl".

Davis was likely better known then, and is still more remembered, for his journalism, but he wrote quite a lot of fiction as well, much of it very successful. (To be sure, there are those who would suggest that some of his journalism was fiction as well!) The only book of his I can find on the Publishers' Weekly fiction bestseller lists (the top ten of each year) is Soldiers of Fortune, the #3 bestseller of 1897. But the book I have is from 1903, The King's Jackal, which comprises two novellas, "The King's Jackal" (30,000 words) and "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" (17000 words). The publication history is a bit complicated, and worth addressing as it hints at some of the publishing world of that time. "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" was written in 1891, and sold to the McClure syndicate for serialization -- presumably it appeared in various newspapers (the Boston Globe being one of them). That same year it was published in a collection, Stories For Boys (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1891); and again in 1896 in another collection, Cinderella and Other Stories. (At a guess, the latter book was considered for adults, while Stories for Boys was marketed for children, so "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" was being repositioned as an adult story (which it surely is) in the second collection.) "The King's Jackal" was serialized in Scribner's Monthly in 4 parts, April 1898 through July 1898. A book edition came out from Scribner's that same year. Finally, in 1903, "The King's Jackal" and "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" were reissued together as The King's Jackal, also from Scribner's. The copyright page for that book, which is the one I have, duly reports "Copyright 1891, 1896, 1898, 1903".

(Let me add thanks to the help of Endre Zsoldos, Denny Lien, Richard Fidczuk, and the excellent resource unz.org in clarifying this complex publication history.)

Todd Mason noted of a couple of previous books I reviewed in this series that the covers appeared to be Gibson Girl covers. (I don't know if those covers were actually by Gibson or derivative of him (or even of someone else like Harrison Fisher).) (Indeed, I saw a copy of Harrison Fisher's American Beauties (1909) at an antique mall in St. Joseph, MO, this past weekend, and Fisher strikes me as wholly as important as Gibson in promulgating a turn of the century image of American women.) The King's Jackal truly is illustrated by Charles Dana Gibson. My copy doesn't have a dust jacket, but I've turned up a couple of images of the original dust jacket and it is indeed by Gibson (a reproduction of the frontispiece art from my edition). Above I show (somewhat pointlessly) a picture of the cover of my edition (which is just the Charles Scribner's Sons monogram, really), plus pictures of the title page and frontispiece.

"The King's Jackal" is about the exiled King of Messina. Messina of course is a major city on Sicily. In this novel, it is said that the Republican movement in Italy kicked the King out, and also made the Catholic Church illegal. I don't know if this corresponds very closely to history. It doesn't seem to jibe exactly with the events portrayed in one of my favorite novels, Giuseppe di Lampedusa's The Leopard (one of the greatest novels of the 20th Century in my opinion), which is about a Duke in Sicily at the time of the Risorgimento.

Anyway, the King is actually fairly happy to be exiled. He didn't care for the burdens of actually ruling his people, nor did he care for his home. He spends his time in Paris and Tangier and such places, with his mistress and a few fellow exiles. He's a thoroughly nasty man, corrupt, a sexual predator, lazy. He's also running out of money, so he has hatched a scheme to raise a lot of money from loyalist families and from monarchists in general, and to stage a fake invasion of Messina which will fail. Then he'll keep the rest of the money.

The only problem is that a couple of his associates are true believers. These include the title character, Prince Kalonay, called "The King's Jackal" because out of misplaced loyalty to the King he has assisted cynically in his debaucheries. But he has been "saved", as it were, by Father Paul, a monk who is wholly devoted to restoring the Church to Messina. The King is worried that Prince Kalonay and Father Paul, in leading the expedition to Messina, might actually succeed -- so he has had his mistress betray the plans to the General of the Republican forces.

A further complication is Patty Carson, a beautiful young American woman, a devout Catholic, who has pledged a great sum of money to Father Paul to restore the Church. The King's problem is twofold -- one, to keep Patty from figuring out the deception, and, two, to try to get his hands on the money, which she would prefer go straight to Father Paul.

Perhaps predictably, Patty Carson and the Prince Kalonay fall rapidly in love (without revealing their feelings to each other). Kalonay, in particular, considers himself unworthy, due to his previous corrupt ways -- but perhaps if he is successful in his expedition to Messina, he will have restored his honor sufficiently. (The King, meanwhile, considers raping Patty Carson as part of the project, and also because he seems to regard it as sort of his droit de seigneur. He really is a nasty man.) Meanwhile, an heroic American reporter shows up to cause further problems for the King. This is Archie Gordon (who, one thinks, might be modeled in the author's mind on himself), who inconveniently is well acquainted with Miss Carson. Gordon is horrified that Patty is involved with a group of people he knows to be reprobates ... and then he runs into a spy for the Republican side of Messina ... Will he queer the whole pitch by finding out the real plans of the King? Or can Patty convince him to support her goals? Or ...

It ends more or less as one might expect, though curiously (and, I think, correctly), at the psychological climax -- we are never to know how things really turn out, but we do know how Prince Kalonay and Patty Carson and even Archie Gordon are changed, and what they plan to do. Not great stuff but fairly enjoyable in its way.

"The Reporter Who Made Himself King" is cynical as well, but in a different and much more comical way. The protagonist is another journalist named A. Gordon -- A for Albert in this case. He's a young pup just out of college, and desperate to find a war to cover, but there are no wars on the horizon. So he decides to write a novel instead, and jumps at the chance to serve as secretary for the newly appointed American Consul to the remote and tiny Pacific island Opeki. On arriving at the beachfront village where lives the tribe with whom the US apparently has established tenuous relations, the Consul immediately quits, leaving the job to Albert. His only assistants are a very young telegraph operator for a nearly defunct telegraph company, and two British seamen, deserters. Soon he realizes that war threatens, in the form of another tribe, which lives in the interior hills of the island and periodically raids the coastal tribe.

Albert convinces the local King to start an army for defense purposes, but when the hill tribe invades, things don't go quite as planned, mainly because a German ship has shown up with the intention of planting their flag on the island, and they have negotiated with the hill tribe. Albert manages to convince the Kings of both tribes that that isn't a good solution, and he gets them, implausibly, to agree to make him King temporarily. And then he manages, more or less, by accident, to provoke a hostile response from the Germans. Which would be no big deal, except the telegraph company, on receiving Albert's report (his first war correspondence!) decides to rather exaggerate what happened, risking starting a war between the US and Germany.

Again the story ends more or less at the climax -- when we realize exactly what sort of fix the characters have got into, but not how things will end. Which works out fine in this case as well. Here Davis' intent is more purely comical, along with a fair amount of satirical comment on the influence of the news media on national relations, and their culpability in fanning the flames of war (something Davis himself was accused of later). Again, not a bad story, fairly funny at times. (And, I must add somewhat obviously, somewhat racist in its depiction of the natives, though perhaps this is blunted a bit because none of this is really intended to be taken at all seriously.)

Thursday, May 29, 2014

Old Bestsellers: Laughing Boy, by Oliver La Farge

Laughing Boy, by Oliver La Farge

a review by Rich Horton

I don't know for sure that Laughing Boy was a major bestseller when first published in 1929 -- it doesn't show up on any of the bestseller lists I can find (which typically list the top ten each year). But it probably sold reasonably well, and has kept selling at some level for quite a while. It seems to be still in print, with the most recent edition from Mariner Books in 2004. Most importantly, it won the Pulitzer Prize in 1930. It was made into a movie in 1934, by most accounts not too successfully. (It starred two Hispanic actors, Ramon Novarro and Lupe Velez.) So, it's not precisely forgotten, but it has somewhat dwindled from the general consciousness over time, in part because Native Americans tend to resist (somewhat reflexively) any depiction of Native American characters by outsiders.

Oliver La Farge, full name Oliver Hazard Perry La Farge, was born in New York City in 1901. As his full name suggests, he was the grandson of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, famous for winning the naval Battle of Lake Erie during the War of 1812. La Farge was also a descendant of William Brewster, spiritual leader of the Pilgrims of the Mayflower. (I will note by the by that I too am descended from a Mayflower passenger, though my ancestor, Richard Warren, is much less significant (and he apparently was not a Puritan).)

La Farge attended Harvard, receiving a Bachelor's and a Master's. He was an anthropologist, and spent time in Central America and Mexico, discovering a couple of languages then unknown to Europeans, and doing important work on the Olmecs. But his most significant work was with the Navajos, on the reservation (or Navajo Nation) in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. The introduction to my edition of Laughing Boy claims that Indians of other tribes thought La Farge was Navajo (though likely no Navajo thought the same). He was an advocate for Native American rights and for some time was President of the Association for American Indian Affairs. He died in Santa Fe in 1963.

Laughing Boy was his first and by far most successful novel. I had encountered one previous story by him, "Spud and Cochise", which appeared in La Farge's collection A Pause in the Desert (1957) and was reprinted in the December 1957 F&SF. I saw it when it was featured in Spider Robinson's 1990 anthology The Best of All Possible Worlds. The conceit for Spider's book was that he chose several of his favorite stories, and the authors of those stories each chose a personal favorite as well. "Spud and Cochise" was Larry Niven's choice. I remember enjoying that story, which is why I picked up Laughing Boy when I saw it at an antique mall. My edition is a 1951 Pocket Books reprint. The official first edition appeared in November 1929 from Houghton Mifflin, but the "true" first appears to have been the Book Club edition, from the Literary Guild, in September 1929.

Laughing Boy is the name of one of the lead characters, a traditional Navajo, in about 1915. He is a young man, a silversmith of some modest note, and he comes to a dance at the southern part of Navajo Nation. There he finds himself entranced by a girl he doesn't know -- a very beautiful but unconventional young woman, called Slim Girl. Before long they have decided to marry, despite the misgivings of Laughing Boy's uncle.

We soon gather that there is a dark side to Slim Girl's life. She insists that the couple live isolated from the rest of their society, near a reservation border town, into which she disappears every so often. She has a fair amount of money and wants to earn enough to set them up well. She also wants Laughing Boy to teach her the traditional ways of Navajo society, such as weaving and general manners. The reader soon learns that she grew up in a White milieu, and grew discontented with American ways, particularly after she was seduced and made pregnant, then cruelly rejected by the missionary priest who had befriended her. After a miscarriage she became a prostitute, eventually becoming the mistress of a rich cowboy. Her plan is to take as much money from that man as she can, then move with Laughing Boy back to his true home. All this is unknown to Laughing Boy.

The story is structured, then, as pure tragedy -- their inevitable doom is clear from early on. And so it goes, quite affectingly. For all her flaws, we sympathize with Slim Girl, and Laughing Boy is a very likeable character. The resolution is powerfully portrayed. I enjoyed the book a great deal.

For all that one does wonder how well a New Yorker from a privileged family really understood Navajo culture from the inside. From my (ignorant) perspective, La Farge seems to do a good job, but I'm sure he got things wrong, and for all his good intentions there is a sense of something just a bit like patronization in his depiction of the Navajos. He's clearly on their side, but -- I don't know. That said, I suspect a 21st Century American Indian (especially a non-Navajo) would have difficulty as well -- it's quite clear that to a great extent the Navajos of Laughing Boy's time were isolated from the main stream of American culture much more than reservation Indians of today are. So -- an interesting and moving book, with a lot of depictions of Navajo life -- the dances, the marriage customs, the weaving and other artwork, the horse's place -- that ring true to my ears. Did it deserve the Pulitzer if books like The Sound and the Fury and A Farewell to Arms (not to mention Look Homeward, Angel, not a book I'm a partisan of) appeared the same year? I'd say probably not -- but I did enjoy it.

Thursday, May 22, 2014

Old Bestsellers: Portrait of Jennie (and One More Spring), by Robert Nathan

Portrait of Jennie (and One More Spring), by Robert Nathan

Portrait of Jennie (and One More Spring), by Robert Nathana review by Rich Horton

This blog is about Old Bestsellers, and Portrait of Jennie certainly qualifies as such. But it's also to some extent about "forgotten" books, and in this case I'm not quite as sure Portrait of Jennie qualifies as "forgotten". But surely less well-known now than it once was. It does have the advantage of having been made into a reasonably successful movie. That said, I remember a panel at a convention some years ago about "Authors in danger of being forgotten". Peter Beagle was one of the panelists, and he cited Nathan as one writer he thought was on the way to being forgotten who should be remembered. (He also credited Nathan as something of a mentor to the young Beagle, and as an influence. You can definitely see the influence of a novel like One More Spring in Beagle's A Fine and Private Place, I would say.)

Robert Nathan (1894-1985) was a quite popular novelist in his time, and he had a very long career: his first novel appeared in 1919 and his last in 1975. (I remember seeing that last novel, Heaven and Hell and the Megas Factor, in bookstores when I was first buying books.) Besides Portrait of Jennie his best known work, also made into a well-received film, is The Bishop's Wife. In the SF field he is slightly known for his 1956 short story "Digging the Weans". His cousins included Emma Lazarus, who wrote the poem ("The New Colossus") on the Statue of Liberty; and Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo. He married seven times.

Portrait of Jennie is a very short novel at about 32000 words. (Most of Nathan's novels were quite short.) It was published in 1940, and made into a movie with Joseph Cotten and the appropriately named Jennifer Jones in 1948.

It's an odd and very haunting book. It fits into the category of "timeslip" novel, one of the most common SF tropes used by non-genre writers. (Other examples include Sumner Locke Elliott's The Man Who Got Away, Audrey Niffenegger's The Time Traveler's Wife, perhaps you could add Martin Amis' Time's Arrow or Ken Grimwood's Replay.) I found it extremely beautiful and moving, though I don't think Nathan quite managed the ending: which isn't to say I can see a better answer. Indeed, even if I don't think the book perfect, I love it in a way that I perhaps don't love books that I might think more fully executed.

It's about a young struggling artist who meets a mysterious little girl playing by herself in a park. He befriends her and learns that her parents are high wire jugglers. Then she disappears,but reappears a few more times, always a few years older. After a while the artist realizes how strange things are, and this girl, Jennie, always seems to know. Basically, she seems disconnected from time. The artist's sketches of Jennie give him the break he needs to make his career, but before long Jennie is all he cares about. The book moves quickly to the inevitable ending. Parts of it, as I said, are extraordinarily haunting: the images of the lonely girl in the park bring tears to my eyes as I type. And there are some very fine lines as well. Really a very good book. The movie, by the way, is not bad, though not as good as the book.

I ran across another Nathan novel at an antique mall: One More Spring. It was published in 1933, and it is very overtly a Depression novel, written essentially as the events portrayed occur. And, perhaps as a result, it is rather a bitter book, despite essentially attempting to tell a sweet story. (It was also filmed, though less successfully than Portrait of Jennie or The Bishop's Wife, and Peter Beagle mentioned that it was lost for a long time, but that a print had been found shortly before the convention I saw him at, and he (Beagle) had seen a screening. It starred Janet Gaynor.)

The main character is an antique dealer, Mr. Otkar, who has to close his shop because of debt. He is left with one large bed. When a likewise penniless violinist, Morris Rosenberg, shows up, they decide to take the bed to Central Park and live there. After one cold night they befriend a street cleaner, who lets them stay in his equipment shed, in exchange for violin lessons. For a bit they feed on pigeons and such, and contemplate stealing a pig from the petting zoo, but then Rosenberg manages to make some money playing on the street corner. But when Mr. Otkar tries to steal from a restaurant, he instead rescues a young woman, Elizabeth, also stealing. She is a prostitute, but with a heart of gold naturally -- driven to prostitution by destitution. She joins them and the three people spend a (chaste) winter in the park, helped by Mr. Sweeney and his wife, who works at a bank. But the bank fails, and the bank president runs away in despair, ending up at the park with the others. They protect him for a bit, but he ends up turning himself in, and finding that the bank will survive anyway. Rosenberg ends up on his feet, more or less, and Mr. Otkar and Elizabeth realize they are in love, but so disillusioned with the world that Mr. Otkar refuses a job offer from the bank and the two decide to wander across the country, living in fields and parks, and likely starving (the author tells us) the next winter. A sad but often sweet novel, not in any real sense believable (but not asking to be believed), and as I said underlaid with bitterness over the economic conditions of the time. Notable is the cynical portrayal of the bank president -- not actually a bad man, nor even corrupt, but quite oblivious to anyone's distress but his own, despite the fact that his circumstances, while straitened, are not nearly so bad as most people's.

Thursday, May 15, 2014

A Fifties Mystery Novel: The April Robin Murders, by Craig Rice and Ed McBain

The April Robin Murders, by Craig Rice and Ed McBain

a review by Rich Horton

A little break from old bestsellers this week. Instead I'm writing about a detective novel from the '50s.

Craig Rice was born Georgiana Ann Randolph Craig in 1908. Her parents did not want an infant messing with their world traveling, and basically abandoned the child to a string of relatives. Eventually she settled with an aunt and uncle, the Rices. Hence her penname, derived from her surname and her adoptive parents' surname. She was married four times and had three children, had numerous affairs, became an alcoholic, and died fairly young in 1957.

Ed McBain, best known by far for his 87th Precinct novels, was born Salvatore Lombino in 1926 and legally changed his name to Evan Hunter in 1952. (He always said Hunter was the most innocuous "white-bread" name he could come up with, but the name also echoes a couple of schools he attended.) Ed McBain was his usual pseudonym, but he also often published as Hunter, and early in his career published as S. A. Lombino. Though best known for his mysteries, he published a number of SF stories, mostly as Lombino or Hunter but also under a few more pseudonyms. (I have read a couple of the Lombino stories, his earliest, and wasn't impressed, but he got better.) He died in 2005.

Craig Rice's most successful series featured a detective named John Joseph Malone. But The April Robin Murders is from her second series, which featured Bingo Riggs and Handsome Kusak, a pair of small-time photographers who keep getting into trouble and needing to solve mysteries to get out of it. The April Robin Murders was left unfinished at Rice's death in 1957, and McBain finished it and it was published in 1958. The back cover copy of my edition (a book club edition, which I found in an antique store in Union, MO) says that the book was 3/4 finished, but, according to Wikipedia, McBain, that is, Hunter, claimed it was only half-finished and he had to solve the mystery before finishing it. Based on style and pace, I would have guessed Rice wrote rather more than half the book, though I certainly believe McBain came up with the solution.

Bingo is the main POV character. He and Handsome have come to Hollywood to make their fortunes. (They started in New York.) They call their company The International Foto, Motion Picture, and Television Corporation of America, but basically they are street photographers -- taking pictures of tourists and offering to develop the prints for a price.

In Hollywood they go looking for office space and a home; and they seem to succeed easily ... though to the reader it's obvious that they are being taken in by a con man when they "buy" their house. The house, they are told, was once the home of the legendary movie star April Robin. But now it is abandoned except for a rather sinister caretaker. The previous owner, Julien Lattimer, died in mysterious circumstances. But, they learn soon enough, a body was never found, and moreover there are two wives, his fourth and fifth, disputing the matter. The fourth thinks Lattimer is dead (we assume murdered by the fifth wife), and so she should get the inheritance, while the fifth claims Lattimer is alive and so she still gets the property.

In good time there are a couple of further murders, and Bingo and Handsome are in a bit of a pinch, between the importunings of a couple of different conmen, the interests of agents and producers and neighbors, and the suspicions of two policeman, a classic good cop/bad cop pair. The solution is a bit intricate, maybe a bit of a stretch, but not a bad one -- involving (as it should) the mystery of April Robin's brief career along with the stories of Julien Lattimer, his wives, and a couple of other people Bingo and Handsome bump into.

For the first two thirds or so of the book things meander along. The main interest is in the characters of Bingo and Handsome -- neither terribly intelligent, both quite likable, Handsome with maybe better instincts but Bingo a bit more agressive and hopeful. Really all this is very fun -- funny in a rather understated way, a bit sad in that you really like Bingo and Handsome but you can see that they're not at all in control of their lives. Then towards the end there is a distinct acceleration, and a slight change in style, and the characters, though not inconsistent with themselves, seem to change focus a bit. I assume that's McBain taking over, but you could argue that it's more a case of the writer, whoever it was by then, realizing that it's about time to get things moving and finish the story.

Anyway, the novel was enjoyable enough that I'll probably be reading another of Rice's novels sometime in the future, assuming I run across a copy, but not enjoyable enough that I'll eagerly search such books out.

Thursday, May 8, 2014

Old Bestsellers: Beau Sabreur, by P. C. Wren

Beau Sabreur, by P. C. Wren

a review by Rich Horton

Long ago, when I was a teenager, I read P. C. Wren's most famous book, Beau Geste, a story of some English brothers in the French Foreign Legion. I remember enjoying it, don't remember much else ... it was a well-known book (and has been filmed several times, perhaps most famously in 1939 starring Gary Cooper) but I frankly had no idea there were any others.

It turns out there were several sequels (of sorts) to Beau Geste, and some related short stories. I found copies of Beau Sabreur and Beau Ideal cheap, and I decided to read Beau Sabreur, because I saw it referred to as the second of the "Beau Geste Trilogy". This turns out to be inaccurate in a sense, because the story of the Geste brothers ultimately filled (one way or another) 5 volumes (4 novels and a collection). And, as I found out, Beau Sabreur is only a very indirect sequel.

P. C. Wren was an Englishman, born 1875, died 1941. He spent some time in India, mostly as a schoolteacher, though he did serve in the military briefly. He claimed that he spent 5 years in the French Foreign Legion after the deaths of his wife and daughter, but there are no records confirming this, and the balance of opinion seems to be that he made that story up. Apparently the details of Foreign Legion life in his novels are quite accurate, however.

His early books are mostly textbooks for use in Indian schools, and one collection of stories set in India. But he began to produce adventure stories in about 1914. Beau Geste appeared in 1924, and was a great success. Beau Sabreur appeared in 1926. My copy appears to be a US first edition (no dust jacket), published by Frederick Stokes.

The novel opens (after a brief preface in which Wren avers that despite the critical complaints that some of the events in his books are implausible, they all actually happened) with what is represented to be the "unfinished memoirs of Major Henri de Beaujolais". De Beajolais begins, confusingly, with him in disgrace in the brig, punished for going AWOL (to help a woman in a fix) ... this turns out to not be important to the story at all. He jumps back to his enlistment as a buck private in the French Army (a Hussar regiment) -- his Uncle, an ambitious General, insisted he enlist after he left Eton -- apparently to teach him how real soldiers live. After a year he can use his Uncle's influence to get a commission as an officer. And so several chapters go by, mostly humorous in tone, describing his early time in the army, during which two important things happen: he meets a regular soldier who becomes his long-time servant, and he forces out a treasonous fellow soldier.

Then the action jumps forward a couple of decades, and South to North Africa. (This action appears to be set in perhaps the first decade of the 20th Century). De Beajolais, now a Major, is an important figure in the Intelligence branch. His previous two decades of service are briefly described (the reader of Beau Geste may recognize one significant event he was involved with -- I did not remember it, though). He is in North Africa, assigned to deal with the problem of the sudden rise of a dangerous Emir among the tribes of the Sahara. While in Zaguig, a "holy" city that is on the brink of exploding, he meets a beautiful American woman, Mary Vanbrugh, along with her maid Maudie Atkinson. As the city erupts in violence, his duty requires him to slink away, to try to find the mysterious Emir and negotiate a treaty with France. Mary Vanbrugh is disgusted with him -- he deserts the French garrison there (including a fellow intelligence officer, his closest friend), who face certain death. Mary's brother stays in Zaguig to die as well, but de Beaujolais and a couple of guides, along with the two women, escape to the desert, where Mary is disguested again when de Beaujolais chooses duty overy loyalty and leaves Dufour and his Arab servant to die in order cover his (and the women's) escape, after which they are captured by the Emir's people.

Here de Beaujolais attempts to negotiate his treaty with the Emir, but there is a rival in camp, representing another power. And it seems that the Emir is infatuated with Maudie, while his Wazir desires Mary. Will de Beajolais sacrifice the women's virtue for a treaty with France? Or will he sacrifice his own life to save the women? His memoir ends abruptly, apparently revealing the answer to that question.

Then the novel transitions to an account from the point of view of "two bad men" -- the Emir and the Wazir. This rapidly (if implausibly (sorry, Mr. Wren!)) unravels a whole series of mysteries, brings things to a neat conclusion, and also reveals at last the link between this novel and Beau Geste. (Which, again, may have been clear already to readers with fresher memories than me of Beau Geste.)

What to say on the whole? The heart of the novel is a pretty fair adventure story. It begins too slowly, and parts of it are uneven. And, yes, much of it is implausible, but acceptably so for its genre. That said, the attitudes towards Africans are, frankly, racist, if in that sort of fawning "acknowledging their strengths" manner. And it is, after all, a story of colonialism from the point of the colonizers, and it's hard for a contemporary reader not to think, "Hey, these Africans resisting French control? They've got a point!" I suppose, in that sense, the novel is "of its time", which probably contributes to it being rather forgotten today.

Thursday, May 1, 2014

Old Bestsellers: The Changed Brides, by Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth

The Changed Brides, by Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth

a review by Rich Horton

Here we go back a bit farther in time. Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth (1819-1899) was perhaps the single most popular American author of the last half of the 19th Century (almost exactly -- her first novel was published in 1849, and she was still working when she died). It would be fair to say that she is all but forgotten now -- but not quite. Her books are not uncommonly found in antique shops and the like, and I even found a paper written at my alma mater, the University of Illinois, about her most successful novel, The Hidden Hand (1859), in which it is averred that a recent development in women's literature courses is the inclusion of popular novels of the 19th Century.

Mrs. Southworth was born Emma Dorothy Eliza Nevitte, in Washington D.C. (in fact in a house built by George Washington). She became a schoolteacher, but moved to Wisconsin, living in a log cabin, upon her marriage. She had two children, but after only a few years of marriage, her husband deserted her, and she returned to Washington, where she lived most of the rest of her life. She returned to teaching, but began to write stories, and fairly soon became a very popular writer.

She was most associated with the New York Ledger, the most popular "Story Paper" of the day. This was a weekly newspaper devoted to fiction (and some features), published by Robert Bonner. By the late 50s Southworth had a contract with the Ledger for $10,000 a year, in return for which most of her novels were serialized in the paper (sometimes multiple times). Most of her novels also were published as books, but her publication history is complicated, and no one seems sure how many novels she actually published. (The accepted number is "about 60".) For a time she wrote two serials per year.

The book I have is The Changed Brides, which as far as I can find out first appeared in 1869. My copy is an A. L. Burt reprint. No date is given for this edition, but I'd guess turn of the 20th Century, roughly. This book seems to be slightly less melodramatic than some of her others, which isn't to say it totally lacks melodrama.

It opens with three curious arrivals, in driving rain, at a tollgate on the road to Old Lyon Hall, in Western Virginia. The Scotch (as Mrs. Southworth would have it) couple tending the gate recognize one of them: Alexander Lyon, who they know is to be married that night to Miss Anna Lyon, the daughter of General Lyon, the master of Lyon Hall. Another is a woman on foot, a slight dark woman who is apparently pregnant. She is desperate to get to the Hall ... for, she says, she is "Anna Lyon". But how can that be? Anna Lyon is a tall blond woman ... The third is a mysterious man.

Before long the young woman has encountered Miss Anna Lyon ... and then we get an extended (very extended) flashback to the history of these four people. Miss Anna has been engaged to Alexander Lyon, her first cousin (once removed) since childhood. They get along well enough, but they are clearly not in love. Back to childhood ... Alexander's mother engages a housekeeper, a devout Baptist woman, widow of a preacher, who has a 6 year old daughter. The housekeeper keeps the daughter (quite literally) penned up in her quarters for fear of disturbing the Lyon family. Then at Christmas Alexander (called "Alick") comes home (he is perhaps a decade or more older) and takes a fancy to the little girl, and takes pity on her isolation, and before long this girl -- whose name is Anna Drusilla Sterling -- is a pet, almost, of Alick's mother. She fixates on Alick, as the agent of her renewed happiness.

Time goes by. Alick, a generally rather selfish and shallow young man, continues to cosset Drusilla (as she is called), eventually paying for her education. Anna has fallen in love with another cousin, Dick Hammond. But nothing is to be done -- for after all Anna and Alick are engaged. Then, just before the wedding, Alick's father dies ... the wedding must be postponed. Just as the wedding is again scheduled, both Alick's mother, and Drusilla's mother, die in short succession. The wedding is put off again -- and now, what to do about Drusilla? Alick, not happy with the prospect of marrying Anna, whom he doesn't love, and somewhat infatuated with the now quite beautiful, and wholly worshipful, Drusilla, decides on the mad course of a secret marriage to her.

Drusilla is installed in a pretty little house on the DC suburbs, and again is kept isolated, as Alick can't let their marriage become known. Before long he is neglecting her (though he does manage to get her in a "delicate condition", as they said), and, on his Uncle's orders, paying court to Anna. Anna is now a supreme beauty, and out of pride in her beauty and jealousy of Cousin Dick, whom Anna truly loves, Alick begins to hope that something somehow will solve his Drusilla problem ...

Well ... after the requisite delays etc, we are back to Drusilla (who technically is named "Anna Lyon") coming to Old Lyon Hall to try to prevent her still-beloved but unfaithful husband from committing the mortal sin of bigamy. Miss Anna is only to happy to escape her marriage -- but how? (And how, I wondered, did nobody but the Scotch wife at the tollgate notice that Drusilla was some 8 1/2 months pregnant?)

So ... things work out, of course, though only partially -- because there is a sequel! This is called The Bride's Fate, and it appeared, I believe, hard on the heels of The Changed Brides. I haven't read it, but I did peek at the ending of the online version, and I wasn't surprised to learn that -- after even more melodrama -- all works out nicely for the characters.

One thing that bothered me a bit about the novel was pinning down the timeframe. It was published in 1869, but it is surely set before the Civil War. But when? Old General Lyon is said to be 80, and there is a brief mention that suggests he fought in the Revolutionary War. That implies he was born no later than, say, 1760 -- which would put the action (the final action) in 1840. But there is mention of railroad service between Richmond and Washington. I had thought widespread rail use in the US began about 1850, but perhaps there was some earlier? Or perhaps Southworth simply wasn't that careful about the exact time of her book.

What to say about Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth? Certainly she deserved her reputation as a writer of potboilers. She had some of the flaws of the prolific serial writer -- she was very very wordy, and very insistent on close description of dresses and rooms and so on. She tells a lot, instead of showing, especially as to explicating the characters. The prose itself is a bit spotty in quality. Her attitudes are certainly of her time -- Drusilla, who is really the protagonist of this novel, is almost sickeningly submissive to Alick, though he is a weak and at times quite bad man. (That said, in general, I have read, her villains are men, and her women are virtuous -- and for her time, while not a feminist in 20th Century terms, she did argue for more independence and agency for women. One would think her personal situation -- abandoned by her husband with two young children -- shaped those views.) The attitudes towards African Americans are hard to read -- there are three significant Black characters, and all are sympathetic, but they are portrayed as occasionally childish, and certainly there is no hint that their lower class position is inappropriate. (That said, this is Virginia, pre-Civil War (I think), and these characters are all apparently free, and paid salaries, and fairly independent.) Mrs. Southworth was, I have read, a friend of Harriet Beecher Stowe, and while there is no trace of abolitionist fervor in this novel, I get the feeling she was sympathetic to the Northern position.) As for readability -- well, I ended up reading with a continued desire to know what happens. It did hold the interest. But, yes, it could have easily been resolved in about half the page count.

In sum, I don't think she's a writer much in need of a revival. But it's not hard to see that she could have been very popular in her time. (And I confess The Hidden Hand does look worth a try perhaps.) I was amused to read that Louisa May Alcott lampooned Southworth in Little Women -- Jo March reads a writer called S.L.A.N.G. Northbury, and despite her evident failings decides to imitate her, until the Professor (who she later married) advised her to stop writing such pulpy trash. I confess my sympathies here lie with Southworth -- for one thing, Alcott herself wrote some pulpy novels under pseudonyms. (And, yes, I did read Little Women (and Little Men, and Jo's Boys) as a teen, but I had no context to recognize the S.L.A.N.G Northbury target, and I don't recall that incident at all.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)